CTC: Many Families Have Enough to Eat

The most common way people used the Child Tax Credit payments was for food.

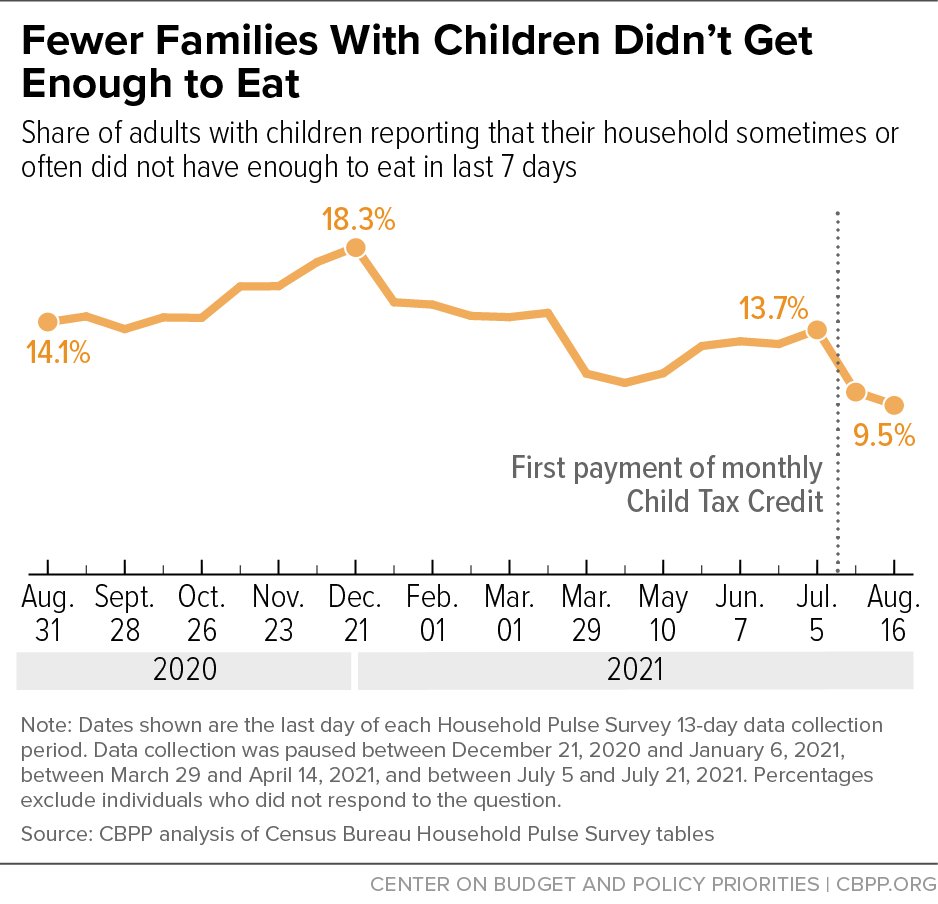

In the month and a half after the federal government began issuing monthly payments of the expanded Child Tax Credit, the number of adults living with children reporting that their household didn’t have enough to eat fell by 3.3 million or nearly one-third, the latest data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey show.

A key reason these payments likely reduce hardships like food insecurity is that the American Rescue Plan’s expansion of the Child Tax Credit made children in the lowest-income families eligible for the full credit for the first time.

Previously, some 27 million children received only a partial Child Tax Credit or no credit at all because their family’s incomes were too low.

The temporary expansion now in place not only made children in the lowest-income families eligible for the full credit but also boosted the credit from $2,000 per child to $3,000 (and $3,600 for children under 6), providing a sizable income boost to families that need it most.

Congress should make it a top priority to extend the monthly payments and ensure that the full credit remains permanently available to children in families with the lowest incomes.

The share of adults with children reporting that their household didn’t get enough to eat fell in each of the first two Pulse surveys taken after the Child Tax Credit monthly payments began, from 13.7 percent in the two weeks ending July 5 to 9.5 percent in the two weeks ending August 16.

The number of these adults reporting that their household didn’t have enough to eat declined from 10.7 million to 7.4 million.

The number of those adults who said their children didn’t have enough to eat dropped by 2.0 million, from 6.6 million in the two weeks ending July 5 to 4.6 million in the two weeks ending August 16.

Parents will often go without food themselves before letting children go hungry, but parents’ hunger and financial worries can take an indirect toll on children and signal substantial financial insecurity that may limit the family’s ability to pay other bills as well.

The remarkable improvement in food hardship follows issuance of the first monthly Child Tax Credit payment on July 15, which provided up to $300 per child under age 6 and $250 for each child ages 6 to 17, as well as continuing economic growth and improvements in food assistance. (A small share of those in the latest Pulse survey, collected from August 4-16, likely also received the second monthly payment, which the IRS issued on August 13.)

Consistent with a strong role for the Child Tax Credit in these trends, adults without children (who don’t receive the credit) saw little change over this period.

Their rate of food hardship has trended downward recently, but the improvement since early July wasn’t statistically significant for adults without children.

The improvement has been dramatic for all racial and ethnic groups but particularly for Black and Latino people.

The number of Black, Latino, and white adults with children in households where someone didn’t get enough food has each fallen between one-fourth and one-third since early July.

These declines are especially important among Black and Latino people, whose food hardship rates were — and remain — about double the white rate.

Specifically, from early July (before the first Child Tax Credit payment) the rate of food hardship declined:

- from 20 to 15 percent among Black adults with children;

- from 21 to 13 percent among Latino adults with children; and

- from 10 to 7 percent among white adults with children.

For Asian adults with children, the rate fell from 6 to 4 percent. The Pulse survey combines other adults – American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, or multiracial – into a single category; their rate of food hardship fell from 22 to 13 percent.

The most common way people used the Child Tax Credit payments was for food.

Families with low incomes were particularly likely to spend the monthly payment on necessities, analysis of detailed data from the first monthly payment shows. Among adults with children with household income below $25,000:

- 57 percent spent their first payment on food;

- 52 percent spent it on utilities;

- 41 percent spent it on clothing;

- 39 percent spent on rent or mortgage;

- 31 percent spent it on school supplies and other education costs such as books, tuition, after-school programs, and transportation to school.

Households with incomes above $25,000 also spent a sizable portion of the credit on these kinds of necessities but less than lower-income families, which face more difficulties affording the basics.

Compared with those with less income, the households with incomes above $25,000 were, for example, more likely to pay down debt or save the funds for later use.